Dr. Christine Hume

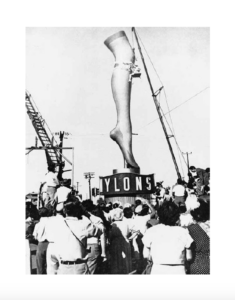

I first came across the Nylon Riots while researching parachutes for a short essay I was commissioned to write for an art catalogue years ago. It stayed with me; no one I know had heard of the Nylon Riots, and the image of women rioting was something I was drawn back to by the woman’s march (which should have been a riot) and drawn to by the #MeToo movement, the Trump presidency, and lifetime of living as a girl and woman. Writing the essay in 2019 felt like a charm against the current erosion of women’s rights compounding the historic lack of women’s autonomy and voice. After the piece went to press, I ran across a resonant passage from Audre Lorde’s “biomythography,” Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (Persephone Press, 1982) We begin, in New Jersey, mid 1950s: “We walked into Gerber’s Department Store looking for stockings for Ginger because Cora insisted Ginger wear nylons to church on Sunday” (130).

Ginger and Audre talk while they “finger” the nylons. This fittingly sexual image turns into an intellectual one of obsessing, musing, ruminating on “Crispus Attucks,” a name that sounds like a spell, a name that destabilizes Audre’s sense of herself as the smartest one in the room. She fingers, she frets; she does not wonder who Attucks is as much as she wonders how she doesn’t know a name famous enough to have a cultural center named after him. Knowledge is a visceral and sexual force.

When Ginger urges Audre to get a pair with her, Audre says, “‘I hate nylons. I can’t stand the way they feel on my legs.’ What I didn’t say was that I couldn’t stand the bleached-out color that the so-called neutral shade of all cheap nylons gave my legs.”

Audre’s description is elaborate:

“The effortlessness with which those materials passed through my fingers made me uneasy. They were illusive, confusing, not to be depended upon. The texture of wool and cotton with its resistance and unevenness, allowed somehow, for more honesty, a more straightforward connection through touch…. I hated the pungent, lifeless, and ungiving smell of nylon, its adamant refusal to become human or evocative in odor. Its harshness was never tampered by the smells of the wearer. No matter how long the clothing was worn, nor in what weather, a person dressed in nylon always approached my nose like a warrior approaching a tourney, clad in chain-mail” (132).

This passage could have easily folded into my essay, “Death, Sex, and Nylon” (issue 49.3), and Lorde atomizes many of its concerns: a rejection of the whitewashing wearing nylons necessitated for black and brown women in midcentury American, an intuitive uneasiness about the fabric’s imitation of human skin, and a visceral loathing for “armor” predicated by binary gender social norms and betrayed by her relentless fingering of the material. Smells like capitalism, stinks like a lie.

As is almost always the case, our subjects magnetize everything around us, orientating us and proliferating possibilities, long after we think we’ve moved on.